It has come to my attention that some readers of

A Fine Dessert have found the depiction of slavery troubling.

Every reader is entitled to their response and I don't expect to say anything which will change those concerns. I would, however, like to explain the choices I made so that a newcomer to the book might not be deterred from reading it and so that they may come to their own conclusion.

Here are some of the objections I read in the comments section of the

Horn Book blog, Calling Caldecott.

"Based on the illustrations, there are too many implications that should make us as adults squirm about what we might be telling children about slavery:

1) That slave families were intact and allowed to stay together.

2) Based on the smiling faces of the young girl…that being enslaved is fun and or pleasurable.

3) That to disobey as a slave was [a] fun… moment of whimsy rather than a dangerous act that could provoke severe and painful physical punishment"

1) At the risk of sounding exactly as the writer of one comment predicted, ("But we included something hard! But I researched slavery!”), evidence shows that many mothers were able to keep their children nearby, usually because it suited the plantation owners to increase their workforce. Historian Michael Tadman estimated that one third of enslaved children in the Southern States experienced family separation, which suggests that two thirds did not. Jennifer Hallam writes, in

Slavery and the Making of America, “The bond between an enslaved mother and daughter was the least likely to be disturbed through sale.” This does not imply that those relationships were not constantly under threat. But it seemed reasonable that we might show a mother and daughter working together. I believe the author, Emily Jenkins came to the same conclusion. There is no father to be seen.

By showing an enslaved mother and daughter together, it is certainly a more positive portrayal of slavery than showing them wrenched apart. But it is not inaccurate. And the book is about different

families making blackberry fool over four centuries.

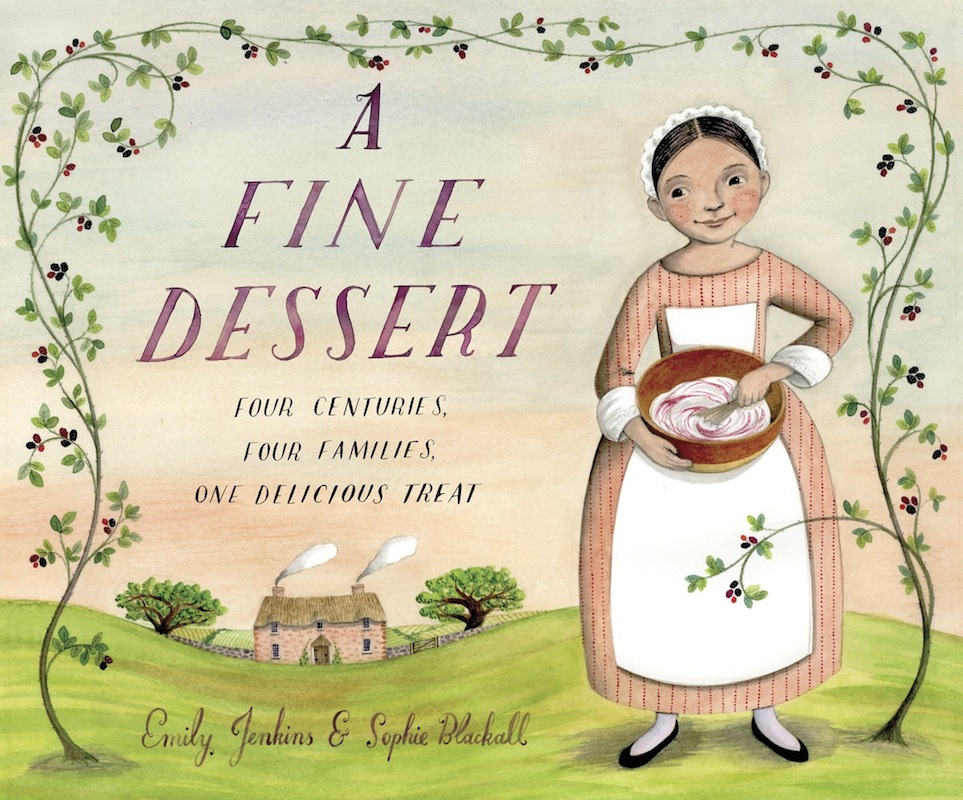

2) I thought long and hard about these smiles.

In the first scene, the mother and girl are picking blackberries. I imagined this as a rare moment where they were engaged in a task together, out of doors, away from the house and supervision, where the mother is talking to her child. It is a tender moment, but the mother is not smiling. The girl has a gentle smile. She is, in this moment, not unhappy. I believe oppressed people throughout history have found solace and even joy in small moments.

|

| click to enlarge |

The second smile comes as the girl completes her task of whipping the cream. It’s hard work, which we see in the middle frame, and the smile was intended to convey pride in completing the task. She looks up to someone, presumably her mother, as if to say, “I did it!”

|

| click to enlarge |

In the next spread, the girl smiles timidly as she enjoys licking the spoon, but looks fearful as she descends the basement stairs.

|

| click to enlarge |

The dinner table scene is set up to show the deep injustice of the situation. The people who worked so hard over the dessert don’t get to eat it. A very small enslaved child pulls a cord to fan the white family throughout the duration of the dinner. The enslaved mother and daughter are somber and downcast. This scene seems to really strike a chord with young readers.

I have shown isolated moments of their day which may appear pleasurable, but I don’t think I have made slavery out to seem pleasurable or fun. As another commenter wrote, “Why shouldn’t a child and her mother, no matter where they are in the world or what their circumstances, share love and a smile in the course of their day? No matter how trying, inhumane or unacceptable the circumstances. Love is the most triumphant of emotions, bringing us through unspeakable trials and ordeals.”

|

| click to enlarge |

|

3) The act of having to hide in the cupboard to lick the scrapings from the bowl is the thing children have responded to most viscerally. They are horrified at how unfair it is. There is nothing whimsical about hiding in the cupboard. It conveys a complete lack of freedom.

Emily Jenkins says in her author’s note: “This story includes characters who are slaves, even though there is by no means space to explore the topic of slavery fully. I wanted to represent American life in 1810 without ignoring that part of our history. I wrote about people finding joy in craftsmanship and dessert even within lives of great hardship and injustice – because finding that joy shows something powerful about the human spirit. Slavery is a difficult truth. At the end of the book, children can see a hopeful, inclusive community.” I would add that this is a book for young children. It introduces issues of slavery in the context of a wider history. It is not intended to be the only story children will read. It does not fully depict the horrors of slavery, but I don't think such a depiction would be appropriate for this particular age group.

The way we look at pictures is incredibly complicated. I cannot ensure my images will be read the way I intended, I can only approach each illustration with as much research, thoughtfulness, empathy and imagination as I can muster.

Reading the negative comments, I wonder whether the only way to avoid offense would have been to leave slavery out altogether, but sharing this book in school visits has been an extraordinary experience and the positive responses from teachers and librarians and parents have been overwhelming. I learn from every book I make, and from discussions like these. I hope

A Fine Dessert continues to engage readers and encourage rewarding, thought provoking discussions between children and their grown ups.

This blog has been edited to add the following:

It seems that very few people commenting on the issue of slavery in

A Fine Dessert have read the actual book. The section which takes place in 1810 is part of a whole, which explores the history of women in the kitchen and the development of food technology amongst other things.

A Fine Dessert culminates in 2010 with the scene of a joyous, diverse, inclusive community feast. I urge you to read the whole book. Thank you.